MUR Blog - The Challenge of Varying Motivation Levels in Volunteer Organizations

Our team of student engineers is diverse in skill set, background, and even motivation levels. As Team Coordinator, ensuring all of the team are engaged enough to show up to work every day has been one of the greatest challenges I’ve faced thus far.

During a one-on-one with one of the engineers, he and I were planning out his next few months; what he, as an individual would be delivering to the team – what his piece of the puzzle was – before the conclusion of the team’s design phase. We’d successfully plotted out tasks, timelines, deadlines and contingencies. By the end of this meeting, my colleague had a clear idea of what he needed to accomplish, and what that accomplishment would look like once achieved. He had his goals, he knew the restrictions, and his responsibilities were written in ink. Just as I was about to stand to shake his hand and thank him, he frowned and sighed, his face lacking the contentment I was expecting.

He looked up from the page and asked me, blunt as a hammer: “Luke, can you give me a carrot and stick, here?”

Thus, began my hands-on education of motivating my colleagues.

My initial thought was “well, the carrot is the experience of Formula SAE, the education of its tribulation, and the glory of its successes. The stick is, if you don’t deliver, we don’t have a race car.” This hardly seemed appropriate. I had assumed that my view was unanimously shared; that experience, education, and race cars were all their own reward. But the truth is everyone is here for their own reasons, and over the year it’s going to be their own personal reasons that make them come to the office every day, their own curiosities that make them explore a concept a little more, and their own passion that keeps them working through the night. I’ve seen this incredible work ethic and love for the sport time and time again. However, the question remains; how do you get everyone on the team working to their best capacity?

The Limitations of Volunteering

For those unfamiliar with the analogy, the ‘carrot and stick’ stems from the most basic staple of persuading someone to complete a task, with a positive reward or a negative punishment. It’s based on the idea of getting a mule from point A to point B, by giving it a carrot as a thank you, or hitting it with a stick if it doesn’t move. Now, as much as I hate referring to my engineers as donkeys, I do love a good idiom.

In the workplace, employees are rewarded with cash bonuses, extra training, promotions, all sorts of fun things. Those who don’t satisfy their roles and responsibilities, well, they’re not so lucky. Volunteer organizations are limited because they can’t afford such niceties, and there’s no pay to dock. Any project manager will tell you that your staff and their ability to perform is another resource that must be managed, but for a volunteer project, their willingness to perform comes into play.

Motivating the Troops

The longer a project goes on, the more likely people will forget why they traded in the comfort of their couch for the welding stool in the MUR workshop. Once they can start to see the end result, people start to work harder, but in the middle of the project it’s the leader’s job to ensure no one feels lost at sea. Everyone has a reason they joined, but sometimes they need help remembering it.

Sometimes it can be as simple as reminding them how important their piece of the puzzle is, having that conversation and validating their feelings. Telling team members that they are making an important difference can mean a lot. “This can save us a second per lap.” “You’re making the car safer.” “This has never been done before, and your innovation will carry on.” Not everyone sees the wood for the trees (I told you I love idioms).

I’ll be candid; I struggled with this soft and cuddly approach. It didn’t suit me at the start. I tried it out during a one-on-one I had with a colleague, where I said: “Without you, we couldn’t even get on track. The car would give out, there’d be fire, death, mayhem, mass-hysteria.” A week later, they were ready to give up. They told me I’d put too much pressure on them, they felt they couldn’t do it, that I should find someone else to fill their role. My attempt to be a cheerleader had left my star player on the sidelines. Not my finest hour.

The best way to ensure the team is engaged is to find where their individual interests overlap with the organization’s goals, and let them embrace it. They all want to achieve something, and I have no problem candidly asking them what that is. In a manner that would make Kennedy roll in his grave, sometimes I have to ask what MUR can do for its people, to mutually achieve the team’s goals and their personal aspirations. Some may argue that the team needs to always be put first, but I believe nurturing someone’s ambitions can reap high rewards for everyone. I’d rather a colleague who’s engaged and filled with purpose over any number of guilt-tripped, uninvolved bystanders.

15 Seconds of MUR Candid Shots

Creating Accountability

No matter how much motivation levels vary, no one wants to do be seen doing a bad job. MUR gives all of its staff the opportunity to succeed by clearly laying out each person’s roles, their responsibilities, and the scope of their achievement. These facts are not kept secret. Everyone has a role, and everyone understands what their colleague’s responsibilities are and who they need to talk to about which component or aspect of the project. The first thing we ask a team member to do as they step into a senior position is write out a problem statement, detailing what they will accomplish over the project life cycle.

Every project has stages, and every stage has a breakdown of tasks. Management discusses this with every person; “How are you going to have this component completed by the end of this leg of the project?” We discuss the goals, we discuss the restrictions, we define the tasks, we put it in writing. Every week we gather as a team and each person has the opportunity to say “this is where I am now, here is where I will be next week.” Like I said, no one wants to be seen doing a bad job. It can be incredibly difficult for those who stand up and say they missed a deadline right after their colleague, who’s only slept 20 hours since last week’s meeting, has presented how they’ve made a breakthrough in their work.

The goal of the leader is not to call these people out and make a spectacle of their failure, but help them ensure that it never happens again. If one of my team members lack the interest or passion to complete an agreed upon task, or they didn’t feel comfortable calling me days prior and asking for additional help, then I’ve failed just as much as they have.

Who Sets the Deadlines?

Setting a project timeline is a skill that not all possess, therefore the project managers are best equipped to define the deadlines. The other side of that coin is that the engineers best know the time they’ll need for the nitty-gritty tasks. Combine that with the fact that these are volunteers who rarely take kindly to being told when to act, and it can all seem a bit of a mess.

The top-down approach, whereby a manager defines the task details and timelines to their subordinates, rarely works in the work place. In our organization, where everyone is already studying 40 hours a week, some are working two jobs, no one is getting paid and the project manager’s experience is laughable in reference to the task to be completed, the top-down approach has its follies.

Instead, the management team creates a general plan for the year, where the concept selection, design, manufacture, testing, racing and evaluation phase all fit into a 14-month design cycle. The lengths of these phases are decided based on the pre-determined team goals and discussed with all the relevant stakeholders, especially alumni. This gives the staff a handful of firm deadlines throughout the year. Finish designs here, have parts made here, assemble onto the car there.

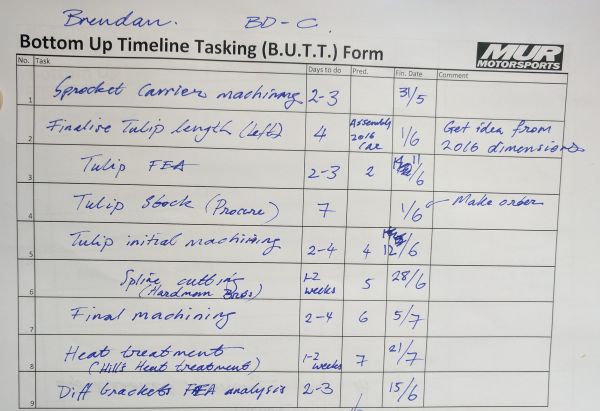

Enter bottom-up-timelining. Individuals detail exactly how they will have the next component ready, day-by-day activities laid out months at a time. Each person discusses with all upstream and downstream systems to ensure they have the relevant information in a timely manner. It’s then management’s job to put contingency plans together and to ensure that everyone sticks to the timeline they not only agreed to, but created themselves. It’s much more likely that a volunteer will complete a goal they set for themselves, rather than one someone set for them. All team members are able to plan their own time, and learn the important skills of timelining.

Example of a Bottom Up Timeline Tasking Form, which all team members fill out regularly.

What if it All Goes Right?

An office full of involved staff creates a highly functioning team, which in turn creates a welcoming and productive environment. In a beautiful feedback loop, engagement begets a context of teamwork, which begets more engagement, which begets race cars.

Creating the proper environment where people can commit to a project, and nurturing each person’s individual interests so they want to become involved can be enough to reach the tipping point, to achieve a full team of highly motivated and outcome focused volunteers.

Want to hear more from us? Sign up here (embed sign up link) and never miss a post! No spam, promise.

About the Author:

Luke Bofinger

Team Coordinator, 2017

Junior Engineer, 2016